Guan Wei

Navigating Guan Wei: Tally Beck

Born in 1957 in Beijing, Guan Wei came of age during China’s Cultural Revolution. After the turbulent events of the late 1980s, there was an exodus of contemporary Chinese artists, many of whom fled to Western art centers such as New York and Paris. In 1990, Guan Wei took up residence in Australia and developed the artistic idiom he had begun in Beijing. As time went on and he became more acclimated to his new home, he began to address cross-cultural issues, environmental awareness and Australian politics. (1)

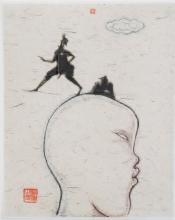

In his 2007 Day After Tomorrow series, Guan Wei continues to demonstrate his fluency in a visual language of his own creation. An often-published quotation of his helps us understand his artistic strategy:

I try to emphasize three elements in my work: wisdom, knowledge and humor. I believe people need wisdom to choose from the many different cultural traditions that confront us everyday; knowledge is the key to open our minds to the diversity of the world; and humor is necessary to comfort our hearts. (2)

Guan Wei’s wisdom and knowledge inform his careful choices of subject matter and create a seemingly effortless balance of a myriad of opposing ideas. His signature style sparks the comforting humor that is simultaneously joyful and enigmatic.

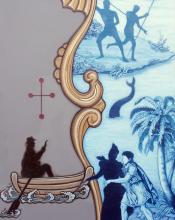

The clarity of Guan Wei’s imagery belies its underlying semiotic complexity. Day After Tomorrow No. 1 (fig. 1) is arranged like two Chinese hanging scrolls that, in juxtaposition, portray a fanciful cartographic image. The left panel is dominated by a triangular land mass protruding from the left. Exotic flora sprouts from the top of the land mass toward a cumulus cloud. On the land mass, a huddled group of Guan Wei’s signature human figures writhe in attitudes of confusion, fear and despair. They lack all facial features except gaping mouths, suggesting haunting screams and wails. Beneath the figures, a red, rectangular seal marks the canvas in the tradition of ancient Guo Hua landscapes. Guan references Qing landscapes once again with an intricate and colored rock formation beneath the seal. The lower, left-hand corner contains another cumulus cloud formation that hides the recesses of the land mass.

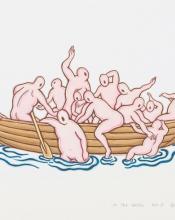

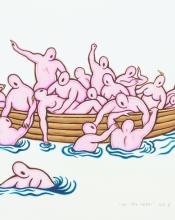

The central white space that divides the two panels bisects a rowboat. At the bow, a standing figure faces the land with a pointing gesture. His pompous, authoritative position suggests the landing of a European explorer, symbolizing Western territorial expansion. A sinewy, fluvial inlet opens on the coast of the land mass where the human figure stands, and it snakes toward the group of the aforementioned huddled figures. The other half of the rowboat lies on the right panel and contains two seated rowers. The figures in the boat have their backs to the viewer, so their faces are not visible. Although their positions and relative sizes bespeak importance and authority, they are portrayed with the same nude vulnerability as the figures in the anguished group.

The right panel is dominated by the sea. One human figure with a gaping mouth bobs in the water, and below, another similar figure embraces two smaller ones, apparently shielding them from the commanding pointing figure. The top of the right panel shows the lower half of a human head with an open mouth, out of which he expels sea foam. This is a reference to the personification of the wind in seventeenth-century European exploration maps, but here, the head is shown frontally. Without billowed cheeks, the mouth seems to be regurgitating sea foam into the sea. This is an example of Guan Wei’s subversion of standardized representation and his creation of an alternative mythology. Below, a sea serpent, again a reference to seventeenth-century European maps, floats with its tail emerging on the left and its head and neck emerging on the right. It recalls the ‘Here be monsters’ images that marked unknown waters. The left half of a cumulus cloud on the edge of the right panel balances the cloud formations of the composition.

While Guan Wei’s iconography has recognizable antecedents in European maps and Chinese landscapes, he presents them in the context of his own personal visual idiom. His distinctive style unites the disparate elements that blend so harmoniously that we do not immediately perceive anomalies. The map-like background, his basic foundation, provides a conducive platform for his iconographic amalgamation. The perspective shifts and disproportionate elements are at home in this format. Guan Wei deftly accomplishes dimension without depth by subtly modeling the figures and formations such that he subverts the cartographic flatness. Furthermore, he delicately varies the tonality of the blue in the sea from dark at the bottom to a slightly lighter hue at the top, giving the vague suggestion of recession and perspective.

Careful balancing also serves to bring unity to the piece. The cloud on the right panel effectively offsets the clouds on the left as well as mirroring the group of human figures. The bisected boat binds the two panels and, consistent with the guo hua idiom, is positioned at the bottom to provide a starting point for our visual journey. Unable to escape wit, Guan Wei creates a charming visual rhyme between the river inlet on the left and the sea serpent’s tail on the right.

In

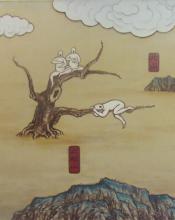

Day After Tomorrow No. 7, he presents four small panels. One is a quotation of the regurgitating face from No. 1, two show contemporary meteorological symbols (the icons for lightning and rain), and one shows a hand with the index finger pointing to the left with a cloud formation behind, recalling the animating Hand of God from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel. Here, he effectively conflates science and mythology while collapsing the historical timeline.Art historian Charles Green compares Guan Wei’s work to Medieval Books of Hours, with its “minute and loving enumerations of recognizable detail, remembered in a nostalgic haze that mimics fragments of apparently utilitarian pedagogy.”

(3) He suggests that, as in Books of Hours, the individual elements escape allegory because “his components seem to have mnemonic rather than narrative functions.” 4 Guan Wei uses these icons to force us to conjure up notions of space, time and identity. His artful juxtaposition indeed defies clear narrative but rather asks us to consider relationships.The artist presents a playground for deconstructionists as he presents his iconography to represent binary oppositions: East vs. West, logical vs. emotional, science vs. myth. Simultaneously, he collapses time and blurs the distinction between past and present. He presents us with mythical Chinese dragons alongside dinosaurs. Conquering explorers encounter frightened inhabitants, but each share the same quivering flesh. Television weather symbols coexist with wind personifications. Guan Wei homogenizes the opposing notions rendering their surface differences irrelevant. What is left is a series of questions about man’s relationship to the environment, man’s relationship to time, and man’s relationship to himself. The cryptic elements of Guan Wei’s language lead to a commentary on the universality of human experiences.

Dinah Dysart, “Guan Wei: Cultural Navigator” in Guan Wei by Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru, Craftsman House, Fishermans Bend, Victoria, 2006, p. 16.

1 Ibid, p. 14.

2 Guan Wei, artist’s statement, ‘Ways of Being,’ curated by Jennifer Hardy, Ivan Dougherty, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 1998, p. 56.

3 Charles Green, “Guan Wei: Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney,” art/text, no. 67, November 1999, p. 94.4 Ibid

Guan Wei graduated from Beijing Capital University, Department of Fine Arts, in 1986. From 1989 to 1992, he attended Tasmanian School of Art of the University of Tasmania in Hobart, Canberra School of Art of the Australian National University, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney as an artist in residency. He moved to Australia under the distinguished immigration program and returned to Beijing as he founded his first studio in 2008. He now lives and works in both Beijing and Sydney. Guan Wei has held more than 60 solo exhibitions internationally. In addition, he has been included in many critically acclaimed international contemporary exhibitions, such as Shanghai Biennial, Cuba 10th Havana Biennial, Australia Adelaide Biennial, Third Asia Pacific Triennial, Japan Osaka Triennial, Kwangju Biennial, etc.

Selected Solo Exhibitions

|

2019 |

MCA Collection, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney |

|

|

Essence, Energy, Spirit, Australia-China Institute for Arts and Culture Gallery, Western Sydney University |

|

|

Divine Comedy, Martin Browne Contemporary, Sydney |

|

|

Retrospection, Turner Galleries Perth, Australia |

|

2018 |

Chivalry, ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne |

|

|

Unexpected Histories, University of Chicago Center in Beijing |

|

2017 |

Cosmotheoria, White Box Art Center 798 Art District, Beijing |

|

2011 |

Spellbound, He Xiang Ning Art Museum, OCT Contemporary Art Terminal, Shenzhen |

|

2010 |

Cloud, ARC One Gallery Melbourne |

|

2009 |

Fragments of History, Kaliman Gallery, Sydney |

|

|

Longevity for Beginners, 10 Chancery Lane, Hong Kong |

|

2008 |

Zodiac, Turner Galleries Perth, Australia |

|

2007 |

Day After Tomorrow, 798 / Red Gate Gallery |

|

2006 |

Other Histories: Guan Wei’s Fable for a Contemporary World, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney |

|

1999 |

Nesting, or Art of Idleness, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney |

|

1998 |

Internal Circulation, Red Gate Gallery |

|

1997 |

The Last Supper, Tokyo Gallery, Japan |

|

1996 |

Return to Paradise, Red Gate Gallery |

|

1989 |

Guan Wei, French Embassy, Beijing |

Selected Group Exhibitions

|

2019 |

Two Worlds, Newcastle Regional Art Gallery, NSW Australia |

|

|

Paper & Ink Language - Nanjing Ink Art Biennale 2019, Nanjing Normal University Museum, China |

|

|

In one Drop of Water, Art Gallery of NSW, Australia |

|

|

Tao Li Fang Fei - Excellent Alumni Invitational, Collage of Capital Normal University, Capital Normal University Gallery, Beijing |

|

|

The Bridges, ACAE Gallery Melbourne, Australia |

|

|

All Fresh, Outstanding Chinese Australia Artists, Intercontinental Double Bay, Sydney |

|

|

The Giant Leap, Casula Powerhouse Art Centre, Sydney |

|

|

Between the Moon and the Stars, Museum and Art Gallery Northern Territory, Australia |

|

2018 |

Cracked – Porcelain, Red Gate Gallery, Beijing |

|

2009 |

Spectacle to Each His Own, Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei |

|

1999 |

Five Continents and One City, Second International Salon of Painting, Museum of Mexico City, Mexico |

Selected Collection

Art Gallery of New South Wales; National Gallery of Victoria; Art Gallery of South Australia; Nillumbik Art Gallery VIC Australia; Australian Art Bank; Powerhouse Museum Sydney; Australian Embassy, Beijing; Parliament House Canberra, Australia; Australian National University, Canberra; Parks Victoria Melbourne VIC; Australia Asialink Art Fund; Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane; Australia BHP Billiton; Sydney Grammar School; Contemporary Art and Culture Centre, Osaka, Japan; State Library of Victoria; Campbelltown Art Gallery Sydney; Tokyo Gallery Japan; Casula Art Gallery, Sydney; University of Queensland; Deutsche Bank's collection; University of New South Wales, Sydney; Geelong Gallery VIC, Australia; University of Tasmania, Australia; Gold Coast City Art Gallery, Queensland; Gold Coast City Art Gallery, Queensland; University of Technology, Sydney; Griffith University, Queensland; University of Western Sydney, Nepean; Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong; Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing; Ian Potter Gallery, Melbourne University; He Xiang Ning Art Museum, China; Lake Macquarie Council; Western Australian Art Gallery, Perth; Monash University VIC, Australia; Wesfarmers Western Australia; Mosman Art Gallery, Sydney; White Box Gallery 798, Beijing; Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney; Yuz Museum Shanghai; Museum of Northern Territory; OCAT Museum Shenzhen China; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; UChicago Smart Museum of Art; USC Pacific Asia Museum; La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia; and numerous private collections

My work has a profoundly felt, if implicitly ironic, moral dimension. In their complex symbolic form, my subjects potently embody current social and environmental dilemmas. They are equally the product of my rich cultural repertoire of symbols and my informed socio-political awareness and art-historical knowledge.

Guan Wei