Wang Lifeng :: Essay

Poetry in History: The Visual Narrative of Wang Lifeng :: Dao Zi

Today’s information age brings with it a significant consequence—the disappearance of historical consciousness and feeling. History was once a modern foundation. It explained the course of modern society’s origin, development, and evolution, but with the development of modern society has come a bombardment of information technology. This bombardment obscures and eventually destroys the context of evolution. On one hand, modern society has made people feel time is speeding by, like everything is happening at once, blurring what is real and illusionary. On the other hand, people feel as if everything is being duplicated, lacking any creativity or trust. Even fine art does not give people a “narrate the past, think about the future” spirit of idealism. The visual entertainment of history utilizes visual imagery, seeping into households and delivering a kind of lethargic “sleeping city culture” television program. As a result, history has all but lost the meaning of its existence. Even so, the rethinking of modern culture and the exploration of modern aesthetics are also emerging from this very ambiguous, dim reality. In China, few contemporary artists have abandoned their historical imaginations and realities. How people understand history very much reflects how they look towards the future.

Since the turn of the new century, Wang Lifeng has persisted in creating works of art with strong cultural and historical consciousness, such as The Great Han Dynasty, The Great Song Dynasty and The Great Ming Dynasty. Recently, using traditional Chinese ink in solid form, Wang Lifeng has produced astounding sculptural installation pieces. Looking at these works by an artist in the prime of his artistic life, how are we to access its value and meaning? Can contemporary visual art interpret history? Is this art different from historical records used by historians? Is it possible for experimental art to express the meaning of history? People read historical records to understand history, but standard historical texts, which are often called primary narration, are actually official revisions of authorized history. It resulted in legitimizing historical knowledge in a unified text, designed to empower authoritarian rulers.

Consequently, contemporary philosophers have asserted that Chinese history is produced by a historiographic culture. Postmodernists believe historical knowledge is neither absolute nor objective. In the end, what exist are contemporary thought and the political creation of relative knowledge. Though primary narration originates from the Scientific Revolution, new advances in science have caused people to doubt its validity,especially its political connotations—the influence of which even science cannot avoid. The historical function of past figures’ playing decisiveroles became diluted, leaving behind a narrative within a linguistic system of representation; yet narration was not the only means of representationin which people could also use description, interpretation and visualization. Understanding the goal of history is also to understand and to seek historical truth, but who and which text decides this truth? Does history belong to the truth of the past or the suspicions of today?

He does not attempt to speak for cultural history; however, he allows cultural history to speak through him with its own unique rhythm, flavour and individual temperament.

Dao Zi

The face is the body’s soul, and culture is history’s face. The expression in Wang Lifeng’s work is not historical time, but rather a kind of rhythmic time. This rhythmic time abandons the dialectics, teleology and objectivity implied in the relation of original time and tries to use a morec onceptualized approach to expressing the richness and pluralism of culture and history.

History paintings, in the context of art history, are recreations commemorating a famous historical personage or event, but history paintings cannot invent history. Primary narration of history is just the painter defining his or her subject matter—in other words, an accepted version from others. Artists use this as a building block to depict the themes that conform to current mainstream ideas and viewpoints. There is little tolerance for artists who used subjectivity and historical creativity in their work. From the beginning, Wang Lifeng has abandoned these models of history painting.

He rejects the so-called grand fabrication of realism—“objectively recreating historical truth”—and instead consciously succeeds in the Chinese tradition of “taking the truths and misfortunes of the past and putting them into today’s works.” As the writer Qian Zhongshu once said, “Poetry is history’s pen; history is at the heart of poetry.” In Ancient China, scholars wrote poems and read history, and, for the most part, poetry glorified history. Poetry, unlike other modes of expression, was the literary vehicle by which historical events, knowledge and meaning were expressed and disseminated.

The expressions of historical events, knowledge and meaning all have specific contexts: their own historical environments. The originality of Wang Lifeng lies in his utilization of visual imagery to construct a historical environment, laying bare deep layers and connotations of the meaning of historical fact. The meaning of cultural history lies in the fact that it exists in intelligible things—things we understand, including the true and the false. Wang Lifeng does not cater to the tastes of his audiences but challenges them.

He does not attempt to speak for cultural history; however, he allows cultural history to speak through him with its own unique rhythm, flavour and individual temperament. Consequently, just by looking at the wispy, faint imagery in Wang Lifeng’s pieces, one realizes what is being presented is anti-narration demanding introspection. Imagery portrays the autonomy of aesthetics and history’s twinkling symbolism—a concept painstakingly pursued by Wang Lifeng that makes his work so unique and multi-faceted. Each of his series (The Great Han Dynasty, The Great Song Dynasty or The Great Ming Dynasty) has been highly purified and distilled leaving behind only the feelings and mood of the main body: quiet but forceful, sorrowful yet brilliant, sincere yet dispirited almost to the point of despair. What it reveals is an artist highly attuned and skilled at portraying culture and history through imagery.

Wang Lifeng: Old Colour, Old Smell, New Medium :: Tally Beck

Wang Lifeng’s artistic trajectory is distinctive and unique in Chinese contemporary art. While many of his compatriots have focused on exploring cynicism expressed in the vocabulary of Pop Art, Wang mines history both real and imagined to concatenate past, present and future in his own personal idiom. An impresario of mixed media, he creates abstract compositions from which readable cultural signifiers emerge.

Wang admits to being a romanticist, and this is evident in the titles he gives to his series. He celebrates graceful elegance, opulent texture and international appeal in The Great Ming Dynasty. Fragments of silk commingle with old documents amid Wang’s expressive oil painting on the canvases. His careful juxtaposition and injection of his own gesture tell us that he is not attempting an objective narration but rather uniting collective memory and personal imagination. Wang’s background in stage design is evident in his work. His compositions suggest a setting and an ambiance. Visual clues give us historical bearings, and his painterly abstraction creates a discernible mood. He effectively controls the elements to evoke a dreamlike vision while reining in the ethereal nebulousness with emphatic historicity.

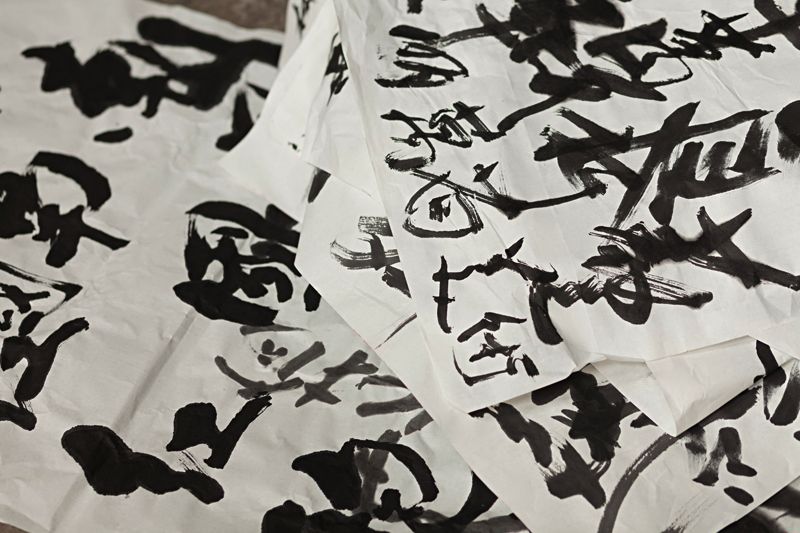

The latest works in The Great Ming Dynasty literally reach out to the viewer. Wang, already having mastered inviting textures, heightens the sensory experience. He inventively incorporates traditional Chinese ink in its solid form into his works. This novel addition adds further texture, dimension and scent to his engaging compositions.

Wang makes his own solid ink according to the traditional recipe. He combines lampblack with gelatine, crushed cloves and borneol, a variety of camphor. After pouring the mixture into moulds of his own creation, he allows it to set. The result is a highly sculptural work of art that carries with it the pungent smell of traditional ink. He describes the effect with the old Chinese saying, “Old colour, old smell,” which suggests the sensory nostalgia experienced when specific sensations transport us to another place and time.

The pieces give a surreal impression. Elegantly styled Ming furnishings seem to break free from the jet-black stone in a Michelangelesque sculptural manner. The texture of the solid ink recalls the abstraction of traditional Chinese mountain landscapes, and the accents of real bronze elements are iconic of China’s opulent, material past. Wang’s wit is evident in his etching of Chinese characters into the solid ink—charming grace notes that reveal his inventive imagination.

While the new works are a further articulation of the artist’s style, they also serve to demonstrate his fearlessness and versatility. These behemoth compositions, dominated by dark black and metallic solidity, subvert the dreamy lightness of the earlier works. Wang concentrates on the mastery of this innovative medium and focuses on the weighty volumes it provides. Cloudy colour gradations and white space give way to anchored, terrestrial solidity. Nevertheless, he imbues these works with an energy that breathes life into them. In spite of the daunting stasis that would seem inherent in this medium, Wang makes them appear fluid and malleable.

Wang’s uniqueness lies in his ability to remain focused on the iconography of China’s past while simultaneously inventing a new visual language in which to portray it. He embraces ambiguity and paradox and transforms them into tools with which he forges his own subjective view of history.